The roles women had in the middle ages were to take care of

their family and husband. Women were taught to be obedient to their husband and

would be punished if she disobeyed. Their marriages were often arranged by

parents; they had to marry at a young age or become a nun. The roles women had

also depended on her social status. Women that were in the working class earned

less than men, while women that were wealthy dedicated themselves to raise the

children, and care for the household. Not only were women not allowed to do as

they want, they were also deprived of education, as people believed it would

interfere with a women’s ability to be a good housewife. However, nuns could be

educated on medicine, science, and music. As nuns could, “They operated

businesses, farmed, made tapestries, copied and illustrated manuscripts,

composed and performed music” (Guerrilla Girls 22). However, “Churchmen who

wrote about female mythic tended to emphasize their inspiration and minimize their

education” (Chadwick 61) creating a limit of education and rank.

Even through the renaissance, women had a difficult time

being known as an artist. As male artists such as: Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo;

had made it more difficult for women to be known as artists, and had created a

male-dominant era. Usually artists would first be an apprentice then join a

guild or union and then open a workshop of their own. But this system was

closed to women. Women could not receive a commission, nor could they legally

own a workshop. Instead, few women had to be born into a family of artists.

During this time, men continued to think of women as “destructive”, “Was

convinced that women were destructive to the creative process” (Guerrilla Girls

31), as they thought educated women were dangerous.

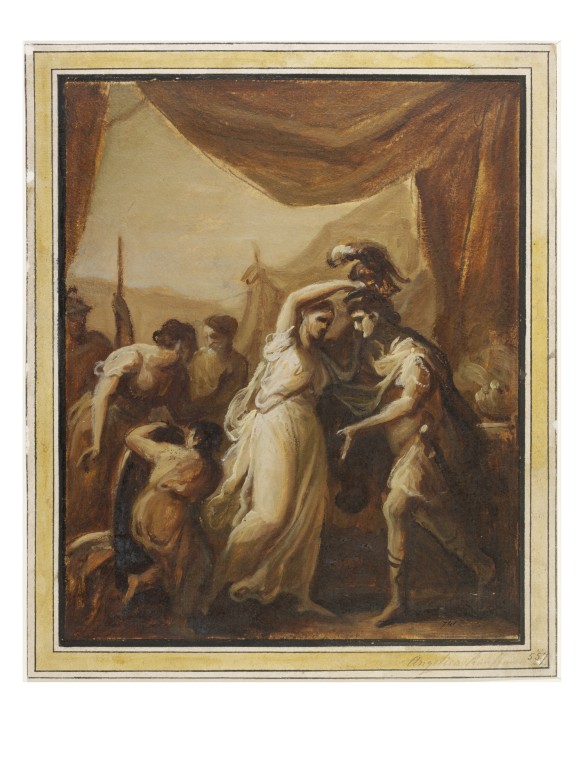

Within the 17th and 18th century women

were continued to struggle. But at this point women’s art work increased. For example,

painter Angelica Kauffmann, did not paint domestic subjects, instead she did

historical art. She was brought to London by a wealthy Englishwomen and sold

enough artworks to buy a house. After being financially stable, she was free to

do more historical paintings. Soon she became part of a social group filled

with famous artists and writers. Eventually she was accepted as a member of the

Accademia di San Luca. Angelica did not let society tell her what she could and

could not paint.

During the 19th century, women begun to have a

stronger affect in art history. Many famous female artists such as, Rosa

Bonheur, Edmonia Lewis, etc.; had left great impacts while facing difficulties.

New tools were used in art, for example, needle work, photography, weaving,

etc. Edmonia Lewis, an African-American and Chippewa, faced hardships of being

accused of poisoning her roommates and was carried by a mob to be beaten until

she was unconscious. She was traumatized and was not allowed to register for

her final term classes, therefore, became a sculptor to redeem her reputation. She

sent her sculptures to people who had not agreed to buy them and “American

tourists flocked to her studio to watch a black woman create art” (Guerrilla

Girls 51). But eventually neoclassicism went out of style and information was

lost afterwards. Edmonia became an example of a woman trying her best to redeem

herself and not to let society hold her down.

Work cited:

“Women in the Middle Ages.” Women in the

Middle Ages - World History Online, www.heeve.com/middle-ages-history/women-in-the-middle-ages.html.

Bovey, Alixe. “Women in Medieval Society.” The British

Library, The British Library, 17 Jan. 2014, www.bl.uk/the-middle-ages/articles/women-in-medieval-society.

The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside

Companion to the History of Western Art. Penguin Books, 1998.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women,

Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.